27 May 2011

Astral is a peer-to-peer content distribution network specifically built for live, streaming media. Without IP multicast, if content producers want to stream live events to consumers, they are forced to create separate feeds for each user. A peer-to-peer approach is more efficient and offloads much of the work from the origin servers to the edges of the network.

This project was completed over the course of the Spring 2011 semester in the Distributed Systems (18-842) course at Carnegie Mellon University, taught by Professor Bill Nace. The Astral team included myself, Fabian Popa, Darshana Advani and Anusha Varshney.

This post is a modified version of the final report the team wrote collaboratively and submitted with the project. It has been reformatted for the web, and rewritten/expanded in certain places.

Live events are an extremely popular motivation for streaming video. President Obama’s 2009 inauguration, CNN served a record 21.3 million live video streams , with as many as 1.3 million concurrent connections at the peak.

Looking at the way those streams were provided (i.e. in-browser) and considering related press releases, we can infer that in order to serve such massive amounts of data, providers invariably need to partner with global content distribution networks (CDNs) like Akamai and Limelight. That’s potentially an expensive proposition for popular events, although less so than we thought at the start of the project. Amazon recently added live streaming support to their CloudFront CDN at quite reasonable prices, making the added complexity and reliability issues of a peer-to-peer solution somewhat suspect.

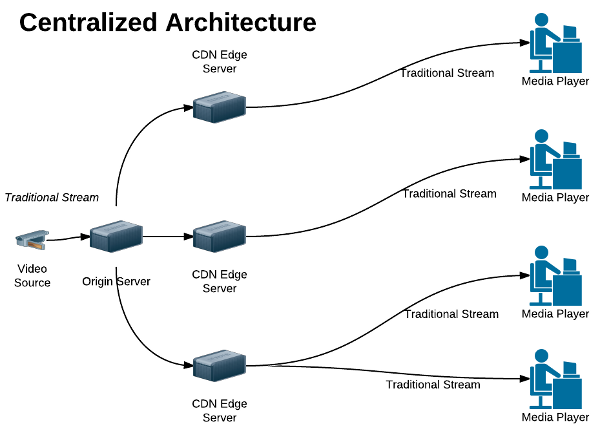

The typical centralized streaming architecture depends on a network of geographically distributed edge servers to which the clients connect. Since IP multicast isn’t feasible over a WAN (due to the many different router configurations between the source and destination), the stream is duplicated once per end user.

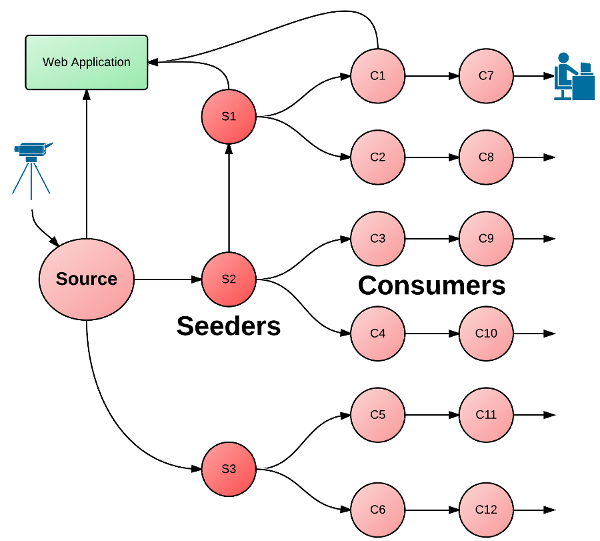

In contrast, a peer-to-peer approach could take the producer’s stream and seed it into the network at different (potentially geographically dispersed) points. The stream’s consumers could then participate in uploading the data they’re viewing to others, using a fairly determined portion of their available bandwidth. A real-world distribution would look much like a telephone fan-out system for school and office closings.

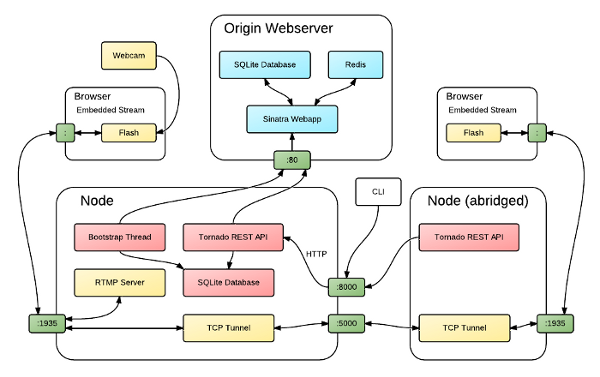

Astral is based on a flexible peer-to-peer client application with a few different user interfaces. The two major components are the centralized web application (astral-web) run by the network operator (implemented in Ruby, with Sinatra) and a Python process running on each individual node.

The nodes each run a small embedded web server and expose a simple (currently unauthenticated) ReST API. The API is used for three things:

A Flash applet in the browser accesses video devices, encodes and finally sends the video into the network using the Real-Time Messaging Protocol. The actual video stream is distributed out-of-band via a chain of TCP tunnels, which connect all of the stream consumers to a Real Time Messaging Protocol (RTMP) server at the source, without ever opening a direct link.

Depending on their configuration, a Python client can act as a stream source, seeder, or consumer (or a combination, bandwidth permitting). The source streams from an external video device through a Flash applet in the browser, which forwards the media stream to the local node and on to the overlay network. The bandwidth limitations of common household Internet connections limit the number of forwarded streams per node to one or two, creating an interesting network graph of consumer chains.

After installing the Astral client, the user visits the URL of astral-web in a browser. This displays a list of all available streams. Each stream has a preview screenshot (not implemented) and metadata, provided by the producer and the source node. When a user selects a stream to watch, the browser communicates their selection to the background process via JavaScript with HTTP requests.

Once the stream is forwarded to the client by at least one other node on the network, the user can view it directly in the browser or in any other streaming media player (by clicking a stream link embedded in the web page).

The Astral client is designed with flexibility in mind. A node can be any of a content producer, consumer or seeder. These three types of nodes make up the clients of the overlay network. The network loosely follows the supernode organization of KaZaa and Skype.

A node announces its presence in the network (and thus its candidacy for stream

forwarding) by sending an HTTP POST request to a supernode with itself as the

data. When a user requests to watch a stream, the node propagates its interest

in this stream through to its neighbor nodes until a node is found that is

capable and willing to forward the content (this is somewhat controlled

flooding, and the strategy could likely be improved).

When a node leaves the network, it performs a few critical shutdown steps to

give other nodes ample opportunity to adjust their stream source or target; it

sends HTTP DELETE requests to any nodes to which it is forwarding a stream,

any child nodes, and (if it has one) its primary supernode. This keeps data as

consistent as possible in the network without the overhead of excessive

heartbeat messages.

The original design of Astral planned to use ZeroMQ for inter-node communication. ZeroMQ is message-oriented library that sits on top of TCP sockets to provide very fast messaging between threads, applications and networked machines. Astral requires occasional messaging between peers, and ZeroMQ would have been a good fit.

In the process of implementing the messaging handling code, however, we realized that much of the logic for routing messages is already implemented in widely available web frameworks. Web services that use the Representational State Transfer (ReST) style are also a natural fit for the type of messages that Astral nodes exchange - e.g. creating and deleting nodes, streams and stream forward requests.

With this insight, we replaced the messaging core with an embedded web server (specifically Facebook’s Tornado). Each node starts an instance of this server listening on port 8000 at startup, and exposes a simple ReSTful API that accepts and returns data in the JSON format. An additional advantage of this approach is that it enabled Astral to use simple HTTP requests in JavaScript to communicate with the node from a web browser.

(The choice of Tornado was one of familiarity, but it’s event-driven nature actually clashes with a few of the Astral API calls. At the moment, it’s possible to deadlock two nodes with a specific series of requests. Tornado should be swapped out for a threaded web server.)

We originally looked at the gstreamer and VLC multimedia libraries, mainly to take advantage of their excellent codec support and stream packaging functionality. Although we were able to get example streams open with both libraries in Linux, it turned out that accessing video devices was not as well supported in OS X (the preferred platform of one of the developers).

Adobe Flash provides better cross-platform device APIs and includes native support for RTMP - these two things made the choice clear for a proof-of-concept. RTMP is an application-layer protocol over TCP with built-in reliability mechanisms (tolerance of lost packets and dynamic packet sizing, negotiated with the server). The stream is encoded with with VP6 video and MP3 audio.

The choice influenced the core design of Astral. We expected to be performing explicit chunking of the stream before sending it off to peers. Since RTMP already provides segmentation and packaging (including meta-information in the header), we were able to benefit from reliability and picture adjustment right out of the box. However, it is arguable that additional reliability guarantees could be achieved in the future by packaging frames directly (e.g. two-stream input on separate paths for immediate failover).

On top of this foundation, we integrated a lightweight Python RTMP server (rtmplite) that acts as a distribution hub for all streams published by the node. All consumers of that stream connect to the corresponding publisher’s RTMP server through a dynamically constructed chain of TCP tunnels hosted by network participants.

(This may be a serious bottleneck, considering that all clients still need to connect to a single streaming server. Our understanding of the RTMP server isn’t complete enough to say how the bandwidth is conserved in this situation. In the future, a more native streaming solution is probably the best course of action, one that allows more precise control over the video frames.)

In a way, we could look at it as pseudo circuit switching, where you share the connection through the system with others. It is guaranteed that the consumer will get the stream they’re viewing over that same connection until a node on the chain of TCP tunnels fails. At that point, Astral immediately tries to reestablish connection by replacing the missing link or potentially constructing a new path.

Reliability is of greater concern in a peer-to-peer distribution network. If any point in the chain fails, the consumer loses their real-time stream. There are a few ways around this:

Neither is implemented in the current version.

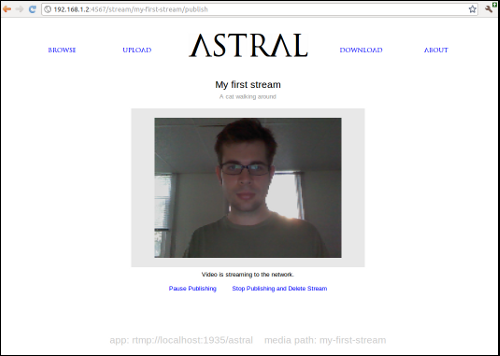

Astral currently implements source streaming from the browser only. The original design allowed producers to direct any existing streaming device or client at a local TCP socket, but a switch to using the Adobe Flash-based protocol RTMP made this more challenging. Our target external device, VLC, does not currently support sending a video stream to an RTMP server. As planned, the streaming interface is extremely simple; it is very similar to hitting play YouTube. The Flash applet also natively supports streaming from any attached device, be it a USB webcam or Firewire HD camera.

The user interface for Astral proceeded exactly as planned. It is deployed to a central location, and accessed via a traditional web browser by all clients. After selecting a stream, the user can view the video embedded in the page via a Flash consumer applet. The page also displays the RTMP server’s URL, so users can connect with another streaming client if they so choose.

Nodes in the overlay network can volunteer to seed a specific stream in order to increase its availability. This requires no special logic - the only difference between a seeding node and a regular consumer is that the seeder does not connect to the stream with a Flash consumer.

Astral clients bootstrap themselves with knowledge of the overlay network obtain via static configuration files, the origin webserver, and finally, their primary supernode. When a node joins the network, it requests a partial list of supernodes from the origin web application. It selects the closest supernode from this list (based on ping round-trip time) and attempts to register with it. If the supernode is already at capacity (currently a hard-coded limit of 100 children), the node continues down the sorted list of supernodes until one accepts it.

If no supernodes are available or none have capacity, a node promotes itself to supernode status, extending the capacity of the network automatically.

Astral has not been tested in a large-scale, simulated environment as was planned. The system has been tested with a 4-node setup, but needs to be scaled up to flush out issues with the overlay network protocol. A potentially good way to test the system is to load a node with many fake node details via the HTTP API.

Astral includes a command line tool for interacting with the local node. This is useful for programmatic integration testing. It controls the node by sending HTTP requests to the same ReST API used by other components. The CLI can display and update stream and node metadata, create new tickets and new streams, and most other node actions.

Video streaming is obviously a critical component of the Astral system. We needed to confirm our initial assumptions regarding native multimedia libraries (VLC, gstreamer) much earlier. Native and cross-platform video device access is possible (other applications are able to do it), but we found ourselves in a time crunch by the time we came to testing the capabilities. These turned out to be non-trivial to operate on both Mac OS X and Linux (the operating systems used by our developers). Using Flash and RTMP for video was a good alternative, but compromised the original architecture vision and has its own drawbacks.

The same origin policy was the biggest impediment to implementing the entire UI in the browser.

The switch to a simpler HTTP API for node communication enabled the browser to communicate directly with a locally running node using simple JavaScript. The original plan called for a browser extension, but the switch made this unnecessary.

However, browsers enforce something called the same origin policy, which

constrains JavaScript requests to the same domain from which the script was

retrieved (it’s a good thing in general for security). The Astral interface’s

JavaScript is retrieved from the origin web server (e.g.

http://astral-video.heroku.com), but needs to connect to

http://localhost:8000 - a clear violation of the same-origin policy.

Fortunately, we were able to work around this restriction by manipulating URL query parameters and with clever interpretation of the queries on the server side. For extended user interaction, a browser extension may be necessary - these have the advantage of being able to query any domain.

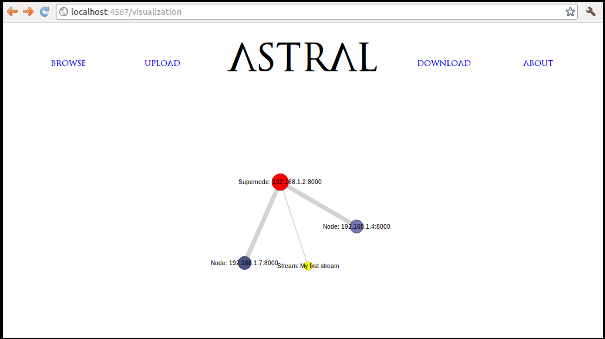

We also implemented a JavaScript visualization of nodes, streams and forwarded streams to get a better sense of the state of the system. The visualization opens a WebSocket (a new web technology in modern browsers for persistent, two-way communication between browser and server) with the server, and the server pushes any updates to its knowledge of the network through this connection. The nodes, streams and tickets are drawn on the screen with using the Protovis graphics library.

Interestingly, the visualizations on each node are not identical due to their different viewpoint of the network, and thus incomplete information. Purposefully, none of the nodes has complete global knowledge.

The project proved that distributed distribution is possible, but we found that the costs of centralized distribution aren’t as high as we initially predicted (which explains its continued popularity). The additional complexity that comes with distributing via a peer-to-peer network may not be worth the trouble, especially considering the extra challenge with collecting accurate statistics about stream consumers. In the industry, the video distribution company Joost dropped support for their peer-to-peer distribution system in favor of a more traditional, centralized approach with Flash in 2008.

That said, Astral proved to be both a challenging and rewarding proof-of-concept project to learn the complexities of building a peer to peer network, as well as the state of the art in video streaming.